Julia Úlehla interview: Dálava, Understories album release

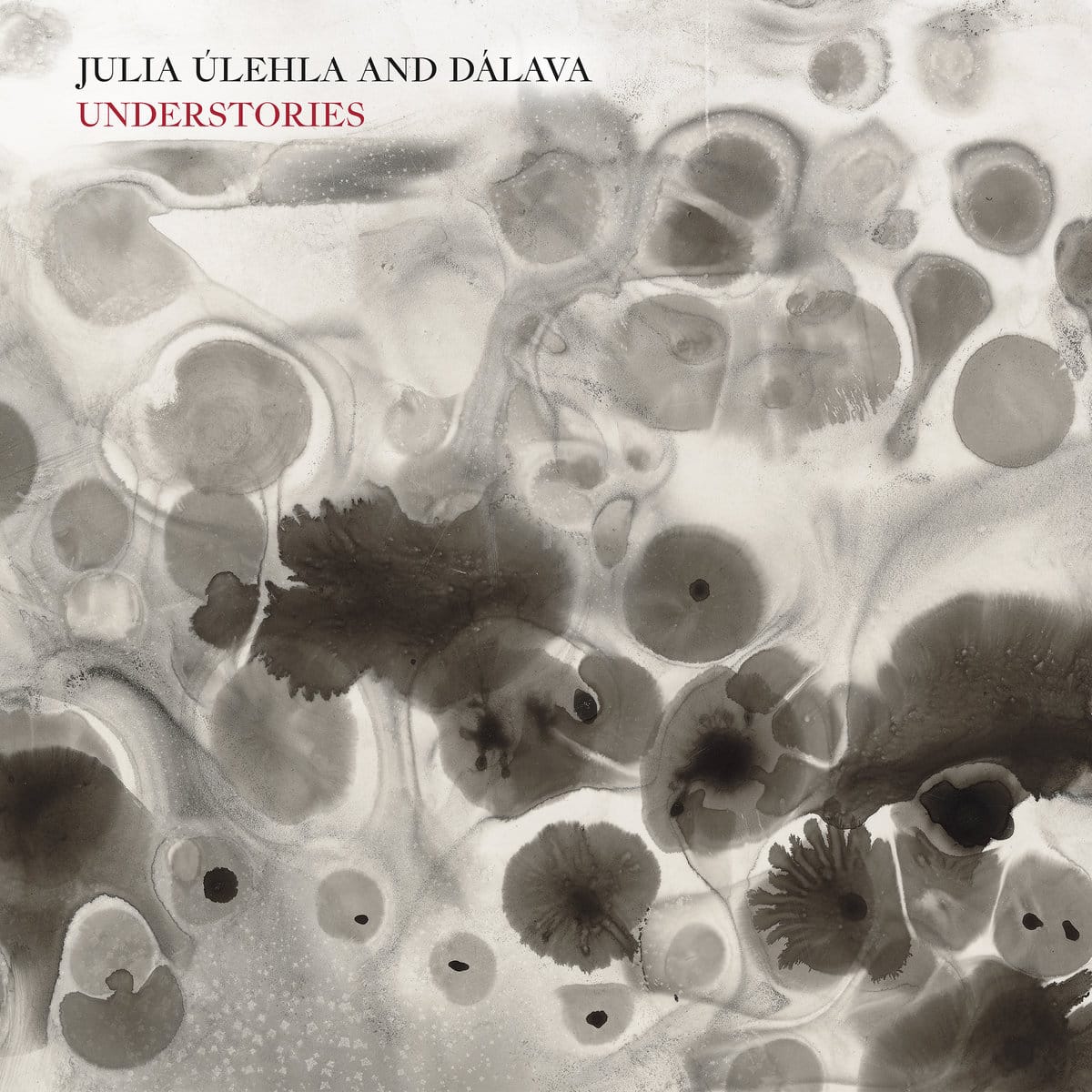

Dálava’s third album Understories with Aram Bajakian, Josh Zubot, & Peggy Lee is out now on Pi Recordings

American vocalist, composer, and ethnomusicologist Julia Úlehla moved to Vancouver for Ph.D. studies at UBC in the mid-2010s. She and her husband, guitarist Aram Bajakian, have lived here ever since with their young family. Úlehla's primary musical project Dálava brings together experimental music with Moravian folk songs; her great-grandfather had collected hundreds of such songs in a posthumously published book titled Živá Píseň ("living song").

Understories is the third and latest album by Úlehla and Dálava, recorded in 2021 and just released on Pi Recordings. I attended the release concert presented by Music on Main at the Fox Cabaret on April 15, 2025. They'll continue playing the new album across three smaller, free-of-charge events Zameen Art House on May 31, June 1, and June 7.

Dálava released its self-titled debut around the time of Úlehla and Bajakian's move. (I first heard Bajakian play guitar in a Capilano University jazz program workshop around this time.) Their second album, The Book of Transfigurations, came out on the local Songlines label and was their first with Canadian-based improvisers: Peggy Lee, Dylan van der Schyff, Tyson Naylor, and Colin Cowan. It earned critical acclaim from the likes of Peter Margasak and Alex Varty, appearing on international year-end lists of 2017.

Úlehla deeply integrates her research and performance. On the Rhythm Changes Podcast three years ago, she told me about finding space in Vancouver "where an intellectual approach and an embodied approach could merge". Understories is another opus brimming with that integrated approach. Bajakian uses various guitars or piano, alongside Lee's cello and Josh Zubot's violin, to accompany Úlehla's singing and digital effects. It's certainly an album to always consume in order and in its entirety; the track sequence has an embedded mythological journey, as she tells me in our latest interview. Please enjoy my conversation with Julia Úlehla below. I made a minimum of transcript editing for clarity.

released May 2, 2025 | Buy Vinyl/CD (Bandcamp) | Not available on streaming

WILL CHERNOFF: So, can we start with the show? I was there, it's a week ago now when we're talking. I had a great time. How did that show feel for you? Sold out!

JULIA ÚLEHLA: Yeah. It felt great. It feels like the start of something new, to be honest, because it's the first time that we've done that material in that order, with thinking about the experience of the whole record as this kind of journey. I’m not even sure really what it does for an audience or for the musicians, and so that whole experience was like, oh, this is what it can do. These are the possibilities. These are the potentialities of these songs.

So for me, it felt super exciting. It's always really lovely to play for a sold-out house and to feel... We put so much care and effort into the record, and so to have people show up always feels like being well-met, that someone wants to receive the thing that you made with love and care.

And also it's just a real treat to play with Josh, because Aram and I perform together all the time, but Josh now lives on Vancouver Island. [Lee didn't join this particular show on April 15.] The opportunity to get together and make music as a trio was really wonderful.

WC: I also heard you at the last year's jazzfest, which was a very different kind of visual environment, me being in the audience, and perhaps also a different performance experience for you.

JU: Yeah. Those were the songs from the record, but we didn't know what they were doing yet. We hadn't made the record, we hadn't put them in a certain order. And the order, at least in my mind, it's a functional order. Yeah. So that's the only other time that we've played it, that's true. But that's interesting, so you perceived it as really different?

WC: Well, it's just different being at the Revue Stage. I was in the front row, and then maybe at the Fox I was a few back or something. But the Revue Stage is darker and it was a more... not sinister, but it was a darker show than the Fox which was a very warm show.

JU: Yeah, I felt that too. I felt that too.

WC: Yeah. And that is reflected in the arc of the album’s tracklist, which is cool too. Because there's the whole thing about “the way down” and “the way up”, right?

JU: Yeah, and I guess that for me is specifically one of the things that I was most surprised by. At the end of the show, people were so happy. They were light, like they felt... there's one lady I even wanna say, she was verging on ecstatic, like she was... the past and the future and the present, and upwards and downwards... she was having a moment, I wanna say, like an existential moment.

Because the record is dark, I think it can go to sinister, but it doesn't have to. And that's the kind of amazing thing that I felt unveiled in that show. Yeah, you can come up, and there can be this levity and you can return to life, in the horizontal realm with this renewed sense of vitality.

WC: Yeah. And especially because it's so improvisatory, one of your shows is gonna be more on the way down, and one of them is gonna be more on the way up. And that's normal and cool.

JU: Yeah. And it's living, like it changes all the time.

WC: Yeah. I listened to your interview on [CBC Radio’s] North by Northwest that was in early April, and among the many stories that I enjoyed you and Aram talking about on there, it was funny to hear a little bit about some of the reactions from people in Czechia, or from here–

JU: Yeah!

WC: –to the music. I wondered if you wanted to retell or talk any more about some of that, because I found it pretty interesting. And I wouldn't have thought about it, but of course you've encountered this when you've taken the music out there.

JU: So, for a long time I was doing a Ph.D. as an ethnographer of this music, and I had a a research-creation focus. My performance of the songs, and even bartering songs or playing with traditional musicians, was part of my research, so I heard a lot of people's reflections on what they felt about it. So yeah, we played with this band from Brno that's also like a avant-folklore ensemble, let's say. It was at this bar, and there's this woman who was so angry and she's... “What does this, what does Julia think she's doing? Her great-grandfather would kill her.” And then there's people who are like, “Oh yeah. You sing like a man. Like, you don't sing like the women sing. You sing like a man.” I'm like, okay, what do they mean by that? What does it mean to sing like a man?

And the thing is, my dad is Czech; my mom is not Czech. The biggest example of a person embodying singing, that I had, was my dad. Maybe I do some gestures like he does, or it's like some subconscious thing that came in... Petr Mička is this amazing, beautiful traditional musician from Slovácko. He had the band and we did a lot of collaboration with them, and he's the one who's like, “No, don't try and sing it like me. Sing it in your way.” In a way it relates to, in jazz, people finding their own voice. You have to find your own voice; you can't take on somebody else's voice. But as long as you have heart and you're sincere, that's what matters most.

Or sometimes people say really misogynistic, nasty words that I will not repeat here. One time someone was like, “Oh, you found the primordial level of this music. It’s like you found the roots of it and you've made a new national culture.” Because people care so much about traditional music, because some people hate it and some people love it, for some people, it has too strong an association with the communist regime, when that was the only music that was allowed to be played on the radio. And they would even change the lyrics and put in Stalinist content, or like ‘good worker’ content. So some people are totally allergic to it. But the long and the short of it is, everybody has an opinion.

WC: What was the only music that was allowed in that time, was it just the folk songs?

JU: Yeah, folklore, like the local folklore, whatever came from the Czech Republic. So not other countries, but just what the folklore was of the nation-state.

WC: Gotcha. Yeah. And the thing that you said about singing it your own way, to me, that matches something that I would understand about the thesis of the Dálava project. It's about how the songs have their own lives, and they have people who have entered and exited the life of the song. So of course, yeah, you can do it your way; and in doing so, you are still connected to the tradition, even though you're doing it your way. That's what everybody else did in theory, over the same song: the song connects to people.

JU: Yeah, I think that's beautifully said. Vladimir, my great-grandfather, he wrote about this exact topic, and he would say people could insert what he called ‘personal seasonings’ in terms of the way they ornament, in terms of the way they phrase, and they could go so far as the culture would allow it. So if it was too wild, it would be rejected and then no one would carry it forward, let's say. This is all within a village context. And so you imagine generations after generations, a singer comes along who adds a unique approach, and it's so influential that other people start to, by osmosis, carry it forward.

But I feel like for me, because I wasn't born in the village and I didn't even grow up in the Czech Republic, I came and had this very different cultural exposure as a kid. Then my references were really different. That was part of the research too. If you go back to the place of origin, what happens? Are you rejected? Are you accepted? Does it impact things, like what are the consequences of that? And yeah, I think it's true. We all have some degree of freedom, but then there also is the community response.

WC: That's fascinating. I have to think about that on my end personally, too, because I don't have somebody in my family like your great-grandfather necessarily. My father's ancestry is the Doukhobor Russian group, and they came to Canada–

JU: Yeah.

WC: –around 1900, and so there's a lot there that I could engage with. And if I did, I'd be asking myself the same kinds of questions that you just addressed, like what would be the reception? And what would you unturn? For sure. But yeah, what would be the reception from the people who I'd still be able to talk to?

JU: Yeah, and it's scary to go back and face people and be like, this is what I've done: what do you think? If you imagine going into a Doukhobor community and... Yeah. But those conversations I think are so important. And that's where the ugly intolerance can come from tropes of cultural purity, which I feel like is always a danger. One of the things about folklore and tradition is that there are these beautiful, amazing songs that have been carried through time, but so often with anything that claims a kind of purity of origin, there's always the danger that it becomes intolerant of what is ‘other’. And so being ‘other’ and going back, and bringing rupture back, bringing divergence back and then being able to talk about it, I feel is a really important cultural practice.

WC: That's interesting, because you used the word ‘rupture’ in the North by Northwest interview as well, so that's definitely a word that represents something very specific that you feel in this context.

JU: Yeah. I think about that word a lot. Yeah.

WC: Okay. Yeah, there's lots to think about there. So, Pi Recordings, you put this album out with them. What can you share about the relationship with them and how that went?

JU: Yeah, so I met Seth [Rosner] and Yulun [Wang], I think it was 2017 in a village in Poland, in something that was WOMEX [a music exposition] adjacent. And so there was something happening in Katowice, which was the UNESCO City of Culture. Because of my work, I was invited to this, it was like a little group of music professionals, and we were together for three days doing totally random things: like eating in this random Polish cafeteria, the cabbage rolls, and being taught to do Polish dances. It was so funny and so bizarre, and we just ended up laughing a lot and talking a lot.

Also there was Peter Margasak, who is a music writer, and so the four of us hung out a lot. And then Peter, I had to give a presentation about my work, and Peter came. I think he was like, “Whoa, what are you doing when you sing?” Something about it, he was interested in. And then he ended up reviewing our work for the Chicago Reader and writing about it, and I think we were on his best-of list for our last record [The Book of Transfigurations].

And then when we had this record ready, Aram and I were talking, and he’s like, you should just write to them and see what they think. So I wrote them and was like, if you wanna listen to this, we just made a record. Just listen and see if you think it would be a good fit for Pi, and no worries. They heard it, and they wanted to put it out.

I like them. I feel that they're good eggs in an industry that doesn't always have good eggs. I also really like... they take this long-term approach with their artists where it's not just a one-off. They will keep putting out work by an artist throughout their career, as long as the artist wants to keep going. That to me is a really beautiful thing too, that you see the work as really like an existential inquiry, always changing and developing and like a process. The way they’ve supported, for example, Henry Threadgill and just seeing the creation process through years, I find it really beautiful. Yeah, I'm super happy to be working with them, and so far it’s going great.

WC: It seems like a great fit from what I've known about the label, from the other similar labels that I’ve worked with or crossed paths with. I noticed in the CD packaging that the music was actually recorded some time ago, right [in early June 2021]?

JU: Yeah. We recorded it during covid, and kind of in a dark moment in covid. It was still when people weren't allowed to get together, and so we had to do social distancing in the recording studio and masking.... we had to push the date back a few times because of all the changing regulations. And then I felt like the record was too dark to release, and I didn't wanna put it out, so we shelved it for a while.

Then about a year ago, we started listening to it again. I was like, oh, actually I don't think it's too dark. I think it's just... it does this dive, and as long as you're willing to do the dive, and kind of surrender to the dive and then come up again, there's nothing harmful about it. Or it’s not... I didn't want to make people feel yucky. It felt like it had an intense darkness, but then it's not actually... there's nothing wrong with that.

I think it does something helpful, actually. It almost feels like it's a way of releasing grief. And then letting it go, and then coming out again. I used to be troubled by it, and then I was like, no, actually I feel good about this. I guess my issue was one of ethics; that if I put something into the world, I want it to be beneficial for the world. I don't want it to cause harm. That was the thing that I was unclear of, or that kept me from putting it out.

WC: Yeah, you knew that it had catharsis, but was it the right time for that catharsis?

JU: Maybe that's part of it. I now think it has catharsis, but I think at the beginning, I thought it was just... I don't know, because it's intense, you know? I feel like it has a potency to it, and I hadn't come to terms with the potency that it had. And now I see that it's actually a productive potency.

WC: Yeah. Where do you say the ‘dive’ is in the sequence? Does it start on ‘the way down’, or does it start earlier or differently?

JU: So the way that I thought about this when we structured it... do you know of the Sumerian myth, the Descent of Inanna?

WC: No.

JU: It's one of the oldest written stories, and it's about a woman, a goddess Inanna, who is known as the queen of heaven and earth. She hears what's called the great below calling to her, and it starts as a whisper and then it gets louder and louder. And so that first track, “open your ear to the great below”, there's something from underneath that's calling you to respond.

And then the second track, “escape velocity”, it's ostensibly a song about a mother and a daughter, and a daughter being sent away from her mother. But I feel like in that song, there's a catalyzing thing that can cause someone to jump out of their habits, mundane ways of being; and it's like you have to have escape velocity to exit, to be able to undertake the journey. Even when a rocket leaves the earth, you think of this bigger body: let's say the mother in the story is like the earth. The daughter is like a rocketship that's launching in order to undergo this transformational journey, or move beyond what you know. You need this escape velocity, so then that's what looses you.

Then “entanglement”, the third song, that's a song where there's girls who are trying to convince their beloveds not to leave. It's like all the things that are like, no, don't go on the journey! Don't go on the journey. Stay here. All the obstacles, all the persuasions that would link you back to habitual life, let's say, where it's comfortable.

Then there's the “queen of heaven and earth”, and that's when you really feel all those attachments to the pleasurable, beautiful things. It's, no, I actually don't want to leave my comfort. I don't want to.

And then comes the beginning of the journey, “the way down”. Those first stages, they’re like preparatory stages that are related. And then this way down, it really goes into a weird, like... where are we going? For me, there really is something very uncanny about that song. Like very eerie, very unknown. “bowed low” comes first. There's like a desperation in that song, or like an upset, and then it goes. “phase transition” is the very bottom. And then “water of life”, a kind of clearing, sacrifice.

So in the story, Inanna, all of those things happen. She makes her descent as she's going down. She has to get rid of all the things that marked her, like her identity. She takes off her crown, takes off her necklace, takes off all her weapons, takes off her robe until she's totally naked. She's in the underworld where she meets her sister, and her sister murders her. Her sister is the queen of the underworld, and she hangs her on a hook. Her corpse is there. And then two hermaphroditic... they're like a combination of male and female beings, who are these divine beings, administer the water of life to her, and that is what brings her back to life and resuscitates her. Then she has to sacrifice something before she can go up again. And so each of the songs follows this kind of mythic descent and ascent. That was a long explanation [laughs].

WC: That's awesome. Yeah, I can see some great musical cues that I could interpret some of that from too. I think all the super-detuned guitar from Aram starts there in “bowed low” and “phase transition”. That's when that effect starts coming into play.

JU: Yeah, for sure. Oh, interesting! Really interesting.

WC: For me, that makes sense when I hear that. Yeah.

JU: Yeah. Also, no one needs to know that there's this mythic reference. It’s not that you have to follow along in that way; I hope it does a lot of different things for a lot of different people. But that was my curiosity of, what is this descent to the underworld and ascent again?

WC: Yeah, that's cool. That's so cool. I wanna finish with something random that I'm not sure is a coincidence, or if there's anything there. Since the Dálava debut and then Book of Transfigurations through now, that's already like a decade, so your life probably looks a lot different now than when you started. I was just gonna ask you how you felt about that. But I noticed something funny that I'll bring up too. When I looked at those three projects... on the first project, all song titles, they're all in Czech. On the second project, they're all bilingual, they're all ‘Czech / English’. And on this one, all the track titles are in English!

JU: That's true! I didn't consciously design that, but thank you for noticing that. Yeah, I think things have changed a lot. When I started, I really wanted to be faithful to the songs. I was a little bit in good student mode, if you know what I mean. This has to be the way that it was, and I have to preserve it and respect its integrity, and not put too much of myself in it.

Then when we made the second record, it was during Ph.D. time, and I wrote like a super long, 30-some-page liner note booklet that had... we've always done text and translations, but I wrote a little bit about each song. The English titles felt like a foray into some of the poetics in my mother tongue, which is English. I felt some kind of liberty to offer forward an English poetics around the songs.

And then partly because this record was made during covid, during a time when it didn't look like travel was going to be possible for the foreseeable future and maybe ever – and everyone was alone in their little insular family bubbles, or... weren’t they called bubbles? Or chosen-kin bubbles – I felt like I was tuned to a layer of reality that wasn't human in a way. The spirits of the songs... the reason I think that a song can contain all of those things, is because sometimes I feel that come through really strongly. It’s like, oh my god, there's an old lady who really wants to sing this song right now. I'm gonna let her sing! Or there's a girl who really wants to sing right now. I'm gonna let her sing. It feels collaborative in singing.

And especially during covid, those are the relationships that matter the most for this record. It wasn't the living human beings who I was going, and doing research and having conversations, and meeting traditional musicians. It was this underworld, quite literally. So I think that’s why those titles... and then because it was this underworld, that's the thing that's really happening: how can you create poetics that do justice to that, or that honour those relationships?

WC: Yeah. No matter how much has changed, like over your decade doing it, it's super cool for me to be able to listen to it and I appreciate it.

JU: Aw, thank you for listening so deeply and hearing all the records, and thinking about it and noticing those things. It's really valuable to me to hear your reflections too.

WC: Thank you!